Fieldwork

Field Trips to Kenyah Villages & Communities

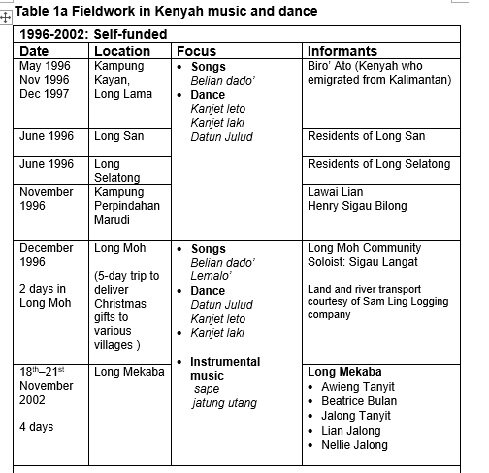

Fieldwork in Kenyah music and dance was carried out in two different river systems in Sarawak, the Baram and the Balui.

(a) Baram*:

Upper Baram: Long San, Long Selatong, Long Moh, Long Mekaba, Long Semiyang, Long Tungan.

Lower Baram: Kampung Perpindahan in Marudi , Long Lama.

*Fieldwork was also carried out in several Baram Kayan villages : Long Bemang, Long Bedian and Long Laput.

Short visits were also made to other Kenyah villages such as Long Ikang and Lio Mato;

(b) Balui/Belaga

Uma Sambop, Uma Badang, Uma Baka’.

The focus of my research was on Bornean songs for music education and choral performances. Initially, I visited the more easily accessible Kayan villages in the Lower Baram. Realising that Kenyah songs, with their wider melodious and harmonic variety, were more suitable for my purpose, I then ventured to the Upper Baram, focusing on the Kenyah. However, as the Kenyah and Kayan live in close proximity and often intermarry, their cultures intersect at locations such as the town of Long Lama and the Kayan village of Long Laput.

Travel in the Baram

Map of the Baram showing locations of fieldwork

Lower Baram : Marudi, about 100 miles upriver from the coastal city of Miri, is the center of administration for the Baram district. When I carried out fieldwork in 1996-1998, the usual means of travel to the lower Baram was by river, via the express boat service from Marudi. This express boat service does not extend to the upper Baram, as many treacherous rapids await after the last station, Long Miri, necessitating the hire of a skillful boatman and a “front lookout”). The express boat from Marudi takes 3 hours to reach the town of Long Lama. To reach other Kayan villages in the Lower Baram, we traveled further upriver to the logging camp at Temala, followed by short road journeys.

Kampung Perpindahan, Marudi 1996

This village, found on the outskirts of Marudi, consists of several sections. The Kenyah section consists of at least 20 Lepo’ Tau families who migrated downriver from Long Moh since the 1970’s. My contacts, Henry Sigau Bilong and Lawai Lian, organized a gathering in the upper storey of a large incomplete house. Immensely proud of their music and dance traditions, they presented an amazing repertoire of songs (mainly belian dado’), dance (datun julud, kanjet laki and kanjet leto), an eye-opening introduction to Lepo’ Tau culture for me.

The video-clip below shows the residents performing the belian dado’ Mudung Ina (That mountain)

Kampung Kayan, Long Lama (May 1996, November 1996, December 1997)

I visited this mixed Kenyah-Kayan community on the outskirts of Long Lama thee times. My main informant , Biro’ Ato ( a Kenyah who immigrated from Kalimantan), a cultural leader in Kampung Kayan. An accomplished singer and dancer, he provided recordings of Kalimantan Kenyah songs and arranged musical gathering involving local Kenyah and Kayan guests as well as migrant Kenyah workers from Kalimantan during our second visit. He also acted as our guide to the Kayan village of Long Laput.

The video-clip below shows a mixed gathering of Kenyah and Kayan at the residence of Biro’ Ato in 1996. The excerpt features a song of invitation to dance sung in two-part harmony.

Upper Baram: In the past, the only route to the Kenyah heartland of the Upper Baram was by river, requiring expert navigation through a series of hazardous rapids. With the advent of timber camps and the ensuing logging roads cutting deep into the interior over the past 30 years, most people now opt for the faster and cheaper alternative: by land over treacherous rough logging-trails, followed by short boat-rides to different villages. The journey overland from Miri to several key upper Baram villages is a dangerous one, beginning with an ill-maintained public clay road which leads to the shanty town of Lapok. This town serves as the main log-pond for the Samling Group of Companies. After this point, as there are no more public roads, vehicles venturing further inland must make use of logging trails owned by Samling. At the time of my field trip in 2009, the roads had reached four strategic locations: Long San, Betao (upstream from Long Mekaba), Long Semiyang and Lio Mato, all situated near timber camps. By 2020, other villages, such as Long Sela’an and Long Moh were accessible by land too.

Long San (June 1996)

Long San, where the late Temenggong Oyong Lawai Jau, paramount Chief of the Kenyah resided, was formerly the center of Kenyah influence and education in the Baram. It is also the location of the main Catholic mission, a major clinic, and major educational institutions for the Upper Baram (the primary school SRB St. Pius, and the secondary school SMK Long San.

This was the first Kenyah village to which I ventured. We (my husband Paul, eldest son Philip and I ) were given a warm welcome despite being total strangers who had the audacity to just show up at the doorstep of the longhouse and ask if they could sing some songs for my research purposes. They generously gathered as many residents as they could, to entertain us with a night of song (belian dado’, kerintuk and suket) and dance (saga potong and saga leto in their dialect).

Long Selatong (June 1996)

After Long San, we travelled to Long Selatong, a short but dangerous boat-ride upriver from Long San as it involved maneuvering through the infamous Benawa rapids. There were more people present than in Long San, as with farms nearer to the village, they could return every night. With more participants, two-part harmony was more evident in their melodious repertoire. Apart from belian dado’, songs of invitations to perform solo dance were sung while the accouterments (a hat and shield for men, a headdress and kirep (fan of hornbill feathers) were brought to the potential soloist.

Learning the finer points of kanjet leto (female solo dance) at Long Selatong, 1996 June

Long Moh (December 1996, June 2004, March 2005, January 2009, December 2013, January 2020)

Long Moh, the fifth Kenyah village from the source of the Baram river, is made up of two separate villages, distinguished by the qualification hulu (upriver) and hilir (downriver). Long Moh Hulu, populated by the subgroup Lepo’ Tau consists of seven main longhouses, each with four to twelve amin, and several ‘single’ houses. The two main longhouses are closest to the river (the headman’s amin is in the first longhouse, while the former penghulu’s family dwells in the second). Along the verandah of each of these two houses hangs an imposing jatung (eight-foot long drum). Long Moh Hilir, populated by the subgroup Lepo’ Jingan, is led by a different headman. Although they maintain a separate residence, identity and hierarchy, the Lepo’ Jingan are fully integrated socially and culturally with the Lepo’ Tau, speaking the latter’s language fluently and cooperating in social, religious, cultural and economic activities.

Until very recently, Long Moh was only accessible by river, as is evident from the large number of boats visible below the houses. Unlike many other modernized villages (where the lower level has been cemented), Long Moh maintains the traditional longhouse structure, keeping the lower level free for storing boats, firewood and other paraphernalia, besides providing shelter for dogs and chickens. The abundance of boats, hunting dogs, firewood and fishing nets are clear indicators of the economic activities and hardships of the village.

A considerable number of amin are deserted for much of the year, as the owners maintain an alternative residence in urban areas such as Marudi, Miri and Bintulu. Secondary schoolchildren attend boarding school in Long San or other schools in town areas, while primary schoolchildren board at SK Long Moh, situated on the opposite bank of the river from Long Moh village (accessible by a very rickety suspension bridge). During my last visit in January 2020, I learnt that 20 families have started cultivating oil-palm in a location near Lapok, about two hours’ drive from Miri, while Kenyah children now account for only 20% of the enrollment at SK Long Moh. Most students come from the Penan community.

One of the first songs I heard in Long Moh was “Tai Uyau Along” (video-clip below) , a comical song about the village fool sung by the children on the verandah in the afternoon, but it also turned out to be popular with adults who sang it at night , also seated on the verandah as they were tired of dancing the tu’ut dado’

The people of Long Moh are renowned for their skills in both song and dance. I have been to this village six times to explore their rich culture. I marveled at the amazing richness of the musical repertoire of this community. the following excerpt from my field-notes in 2004 offer a glimpse of their impressive artistry:

… After refreshments had been served, a group of women formed a line and sang, with accompanying movements, a series of belian dado’, beginning with “Nombor satu, nombor dua”. Sigau Langat soon joined the dancers with “Abe Na’on Nekun”, a melancholic song with a hemitonic tune. Other men joined in and the pace picked up. They went on for nearly an hour, singing, often in two-part harmony, a total of 11 songs. These ranged from slow, sentimental songs to fast, lively ones. Nine songs displayed anhemitonic pentatonic tonality, while two songs, “Abe Na’on Nekun” and “Taroi”, were hemitonic. They ended with a fast, robust version of “Burung Kechin”…. Although the whole “performance” was impromptu, with people randomly joining the line, there was hardly any break in the songs, as if the whole event had been rehearsed. The soloists showed no hesitation in the improvised verses, and the chorus maintained perfect time, pitch and harmony.

In between, several belian burak were sung, followed, by popular request, with Aban Ingan’s (a resident of Long Semiyang who had followed us to Long Moh) delightful rendition of “Pesalau” (a humorous responsorial song poking fun at the thirteen Kenyah villages along the Baram). Everybody joined in the chorus without the slightest hesitation.

Dance: After an hour of belian dado’, the dancers and musicians were ready to perform. The instrumental ensemble consisted of two jatung utang, sape, guitar, harmonicas, even a recorder (instead of the usual flute or suling) and partially filled bottles tuned to ‘so’ and ‘do’. As usual, the first dance to be performed was the datun julud, a choreographed group-dance for women. A line of twelve women gave a polished performance after a twenty-minute rehearsal ‘backstage’ in a nearby amin. They were accompanied proficiently by the ensemble, playing ‘det diet’ repertoire. Each holding a pair of kirep (circlet of hornbill feathers), they performed a set sequence of steps, moving forwards and backwards, and occasionally turning to right and left.

This was followed by both men’s and women’s solo dances (kanjet laki and kanjet leto). I noted that they endeavored to present music and dance in an appropriately ‘traditionally correct’ style. During my previous visit, they had simplified the performance by presenting male-female duets accompanied by the full jatung utang ensemble playing the same ‘det diet’ music. For this occasion, male and female dancers performed separately accompanied by the appropriate sape melodies (hemitonic melodies for women, anhemitonic for men).

Kanjet Laki: Sigau Langat preceded his dance with a magnificent belian tu’ut (introductory song performed before a solo dance), then danced regally, though with less agility than in his performance eight years ago. His voice, however, was still expressive and resonant, and his rendition of the lyrics seemingly faultless. The second performer, Jon Lido, a young man in his late twenties, gave a mesmerizing performance, displaying grace, technical skill, agility and dramatic use of the shield.(video-clip below shows part of his performance)

Festivities were discontinued at 3.00 am, but would resume early the next morning, as declared by the headman, thus giving everybody time to get their costumes. He announced that the villagers would forgo other work commitments in the morning to perform the saga lupa for us. The villagers agreed as they were immensely proud of their carefully preserved culture and eager to give a performance worthy of their reputation. They even chided us for not sending word earlier as this would have given them more time to prepare for a proper performance.

Saga Lupa and Lemalo: The next morning, at about 8.15 a.m., residents began to gather in full costume on the verandah. Soon a group started to wind their way along the verandah in a slow dance, the saga lupa (basic step: step side, close, step-half turn, close, turn back) using recorded music. In half an hour at least thirty dancers were performing the saga lupa along the verandah (women in costume, the men in full warrior regalia with sword and shields). It was a magnificent sight (video-clip below)

Hose (1993:167) describes the Kayan equivalent of the dance: “ … they turn half about at every third step … turning to the right and left symbolizes the alert guarding of the heads which are supposed to be guarded by the victorious warriors ...”.

I spent two weeks in Long Moh in January 2009, accompanied by my son and assistant, Darren Chin (during which we had first hand experience of severe floods ). We learnt much about sambe asal and the mamat ceremony from the late Lian Langgang (described under the section The Music of the Kenyah). My most recent sojourn there was in January 2020, a very fruitful trip (fortunately just before the global pandemic ), during which I gathered much material. Some of the songs I collected then are featured in the new (second) edition of Folk Songs of Sarawak : Songs from the Kenyah Community (2020).

Long Mekaba, Upper Baram (November, 2002)

Long Mekaba, sister-village to Long Moh, lies on the Silat river, a tributary of the Upper Baram. Previously, it was one of the most inaccessible villages due to its location just beyond an especially perilous stretch of rapids. Heading there by river in 1996, everyone alighted from the boat so that the boat-driver could “pole” through the rapids. A rough logging road now circumvents these rapids, offering an uncomfortable drive of twelve hours from Miri, past Long San, to Betao, a logging camp on the upper reaches of the Silat. From there, it is then an easy one-hour boat-ride down-stream to Long Mekaba. This is the route I took in 2002, accompanied by my college student Beatrice Bulan Jalong (who hails from Long Mekaba), Filipino ethnomusicologist Frank Englis and Indonesian anthropologist Dave Lumenta. Beatrice’s father, Jalong Tanyit, is an internationally renowned sape player and at that time the headman of the village (He is now penghulu -regional chief-of the Upper Baram). The video below show excerpts of women’s dance kanjet leto and datun julud accompanied live by Long Mekaba musicians.

Long Semiyang (June 2004, March 2005)

The third Kenyah settlement from the source of the Baram, Long Semiyang was formerly a riverine farming village. With the establishment of a logging camp a few miles away, the situation has changed vastly. It has become almost independent of boats, as four-wheel drives and trucks ply between village and farms daily. The farms are no longer accessible by river. Road access has brought development, but also results in dwindling supplies of fish and wild boar due to encroachment by the projects of urban businessmen.

The residents of Long Semiyang consist predominantly of the Ngurek subgroup, and a sizable number of the Lepo Ke’, a different subgroup who migrated from Kalimantan about 20 years ago. The Lepo Ke’ live in a separate longhouse but mingle socially and combine musically (they are the leading exponents of the lutong kayu) with the Ngurek at musical gatherings.

With Lepo’ Ke lutong kayu players , Long Semiyang, 2005

Baun Lenjau of Long Semiyang playing the keringut, June 2004

Baun Lenjau of Long Semiyang had not played the keringut (nose-flute) for years, but made one especially for the purpose of my recording. It is a very private instrument, played at leisure for the family or purely for self-expression. Baun played a melody associated with the tale of two doomed lovers who elope due to parental disapproval (based on class difference)and commit suicide at Batu Lingep, a rocky outcrop near Long Semiyang. She also sang the associated song, which narrates the story.

Before performing the solo warrior dance kanjet laki, dancers sometimes sing a prelude such as ruti kendusang as depicted in the audio-clip below. The solo part was sung by the late Mat Jau (photo above shows Mat Jau executing a low level pivot turn) in 2004 with all the other villagers joining in the choral response on a tonic drone.

Long Tungan (March 2005)

The longhouse at Long Tungan is a two-storey structure (a design gaining popularity especially among the downriver Kenyah and kayan villages), with the ground level (traditionally kept open for storage of boats and firewood) closed up and cemented. Our visit only lasted for an afternoon, but the residents kindly obliged with a series of five belian dado’ three out of five rendered in two-part harmony. the video-clip below shows the beginning of the song "Lan-e Tuyang”.

Travel in the Balui

Prior to the construction of the Bakun Hydro-electric dam, the only route to Balui-Belaga villages had been by river, past a series of rapids. To facilitate the construction of the dam, roads to the interior had to be built. Thus, some of the previously remote Kenyah and Kayan villages in the Balui are now accessible by road from the town of Bintulu . The building of the dam compelled many upriver villages such as Uma Baka’ and Uma Badang to relocate. The residents had to abandon their homes, farming lands and ancestral graves and move into longhouses provided by government authorities in the Sungai resettlement area.

The video-clip below shows excerpts of three different belian dado’ or badi as they are known in the Balui/Belaga district, sung in Uma Badang, Sungai Asap in January 2008.

Uma Sambop (August 2004, January 2018, December 2018, December 2014, December 2015, March 2018)

When I visited Uma Sambop between 2004 and 2015, it appeared to have the best of both worlds. Located beyond the zone designated for the dam, it still stood majestically on its original site. In 2003, with the construction of a suspension bridge linking the village to the trunk road, it is only 2 ½ hours by four-wheel drive from the town of Bintulu, whereas previously it was a week’s journey by river.

Suspension bridge to Uma Sambop (photo taken in 2004)

Unlike many other villages in the Baram and Belaga, Uma Sambop was thriving, with a healthy increase in population. A 76-door longhouse with 900 residents, it had occupied the present site at Long Semutut, Ulu Belaga, for over 50 years. To accommodate the government clinic, the longhouse, on expansion, adopted an unusual rectangular structure, with a quadrangle in the centre.

However, during my last visit in March 2018, after devastating floods had inundated the village in January, the situation was very different. The villagers had lost many of their belongings in the floods, and the structure of the longhouse was beginning to crumble, with the villagers being unable to source for replacements for the original belian beams and roofing. Many of the villagers heeded the state government’s advice and were in the process of moving to a new site upstream on higher ground. Some were reluctant to abandon their original location, especially as the “new village” consisted of simple one-storey cement structures with none of the graceful character of the original longhouse.

The video-clip below shows the residents of Uma Sambop in January 2018, singing at a gathering in honour of our visiting team as part of the ISME-Gibson award project. (15 of us, including 12 ITE Batu Lintang students. The students acted as facilitators for our workshops on Kenyah and Kadazan songs with the schools, and were also there to observe Kenyah culture).

Kayan villages

Before venturing to Kenyah villages, I had first investigated Kayan music culture, visiting the villages Long Bemang and Long Bedian in April 1996, and Long Laput in 1996, 1997 and 1999, where we observed dance and instrumental music. Dances observed include hivan joh (long-dance) hivan doh, hivan lake (men’ solo dance) and hivan sau kayau Instruments observed include sape, tong (jew’s harp), selingut (nose-flute, Kenyah term keringut) and satung (bamboo zither, Kenyah term lutong). As these instruments and similar dances were also practised by the Kenyah, some details are included below.

1996 Long Bedian: Learning the Hivan sau kayau , a dance accompanied by gongs . Originally performed with dried sang leaves to celebrate the return of a successful head-hunting expedition. This dance was also practiced by the Kenyah.

Long Laput (1996, 1997)

In 1996, Biro’ Ato brought us by boat to the large Kayan village of Long Laput, (about 20 minutes upstream from Long lama) in search of Imang Ajang, possibly the Baram’s last remaining exponent the of the mouth-organ (keluri or keledi , Kayan terms or kedire’ , Kenyah term). Imang was away harvesting durians in 1996, but my son Nicholas and I succeeded in meeting with him for a demonstration in 1997 (during a visit again facilitated by Biro’).

The late Imang Ajang demonstrating the keluri (mouth-organ), Long Laput, 1997